Weekly Project 7: Get Distracted

Your assignment for this week is to get distracted. First, reread Walter Benjamin’s “Theory of Distraction” (pages 211-212 of our reader). Here, Benjamin contrasts the modern experience of distraction with the forms of absorption and concentration that “serious” artworks are meant to solicit. According to Benjamin, we “consecrate” the traditional work of art, making it into something sacred; the forms of attention and reverence we give to the artwork draw from our idea of the sacred. (Indeed, in many parts of the world, the entire practice of making what we now call paintings and sculptures originated in religious and spiritual practice.) But the emergence of mass media such as film, radio, newspapers, and illustrated books introduced new forms of art and new kinds of attention. Distraction, according to Benjamin, was not so much the opposite of attention but the name for the new kind of attention specific to modern media and urban life. The values of distraction and its emergent art forms were distinct from those of “traditional” artworks: trends and cycles in movies, fashion, and popular illustration moved at unprecendented speed. The ephemeral, rather than the eternal, was the thing. Rapid change brought with it new sensations, a new pace of feeling, and thus new possibilities for art and experience.

The urban environment was a key site for Benjamin’s theory of distraction. His major inspiration in this area was poet and critic Charles Baudelaire’s (1821-1867) descriptions of the experience of wandering modern, urban Paris in a time of rapid social and technological change. Baudelaire is the best known expositor of a figure called the flâneur; this term lacks a direct translation, but it describes a kind of aimless wanderer, a person who walks the streets of the city for no precise reason other than to see and be seen. In Baudelaire’s mid-19th-century Paris, simply wandering here and there, following whatever caught one’s attention, could be an activity in and of itself. Writing in the 1930s, Benjamin believed that the distracted experience Baudelaire narrated had expanded and multiplied to include the burgeoning lower-middle and working class of the cities: shopgirls, secretaries, clerks, and laborers.

(The feminine version of flâneur is flâneuse. This term first applied to upper-class women of leisure who wandered the city, but starting in the twentieth century its use expanded to describe the female workers–shopgirls, waitresses, and secretaries–who wandered department stores and high streets to window-shop in their off-hours. If you have ever gone to, say, a Sephora in order to try on make-up or perfume that you have no intention of buying and could perhaps never even afford, then you, too, are a flâneuse.)

More wandering: In the 1950s, the French artist and critic Guy Debord (1931-1994) and a group called the Situationists drew on Benjamin, Baudelaire, and others to develop a type of urban wandering they called dérive. In “Theory of the Dérive” (1958), Debord called it “a technique of rapid passage through urban ambiances.” His guidelines for conducting a dérive reads almost like the opposite of last week’s guide to “having an experience”: the activity is best done in a group, with no particular goal or point of focus in mind. He writes:

“In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there… in the great industrially transformed cities that are such rich centers of possibilities and meanings…”

The real purpose of a dérive was to gather information (in an open and undirected way) about “psychogeography”: how different areas of the city have different feels to them, different “ambiance,” different vibes. Debord’s method: a person can conduct a dérive alone, but a group of 2, 3, or 4 is best. (Five is too many.) Pick a starting point, then walk in whichever direction captures your attention. Get distracted by any and everything. You can take photos if you want, preferably of little things that make no sense but catch your attention anyway. My own belief is that it is better not to focus on facts or interpretations but on vibes.

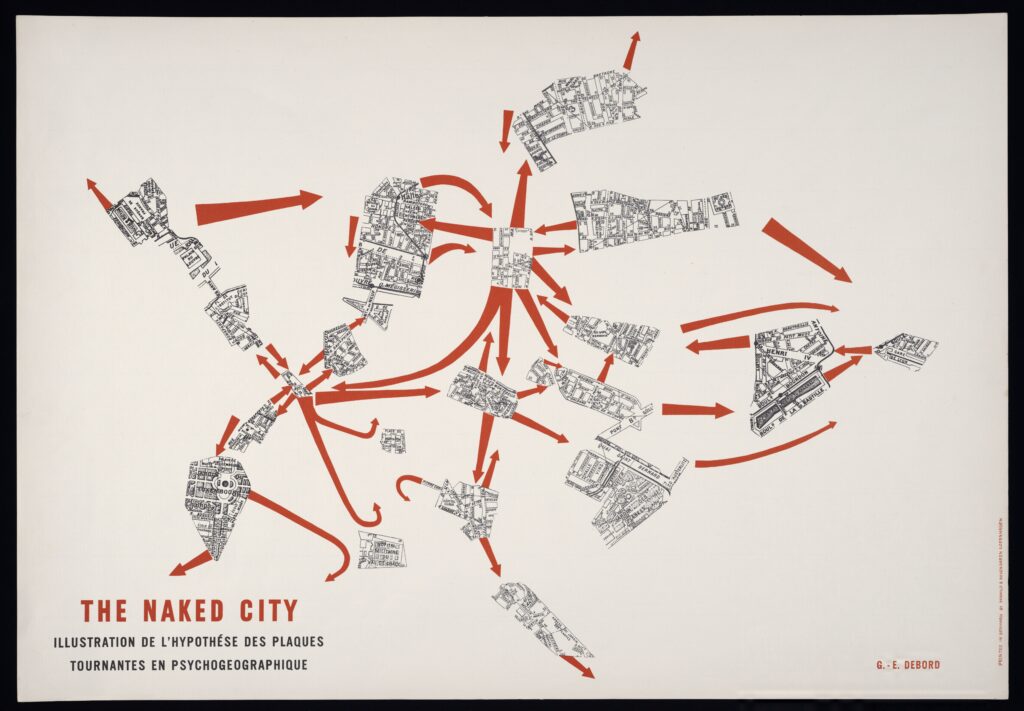

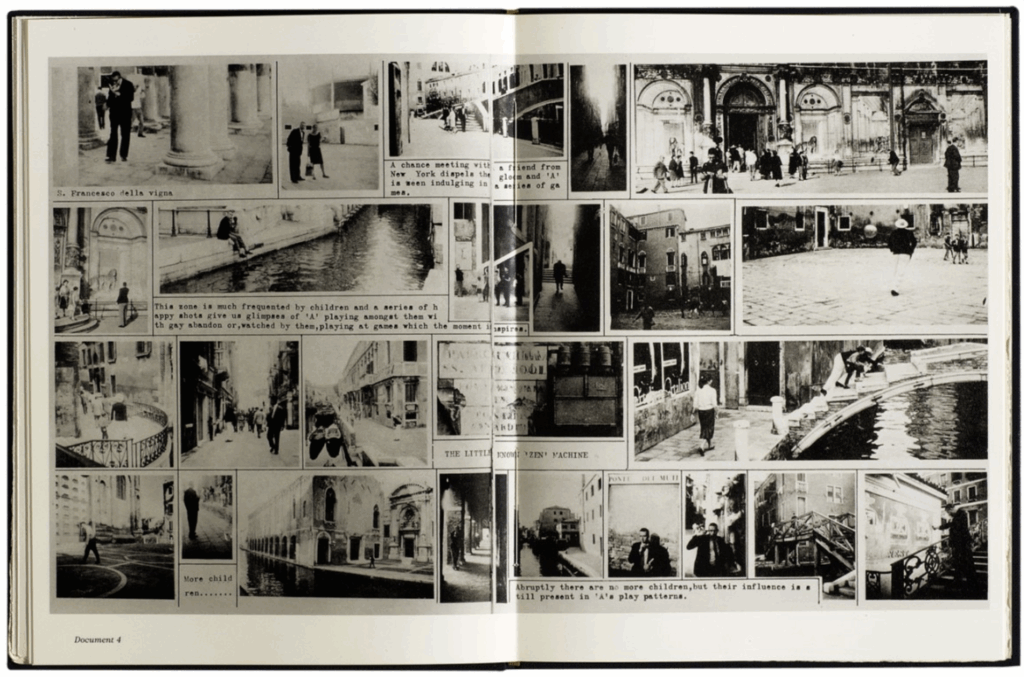

When your dérive is over, you may make something that describes your movements and impressions in a similarly disorganized way. The few reports of Situationist dérive are similar to Baudelaire’s writing on the flâneur in that they expresses an atmosphere without reducing it to an argument or thesis statement. Debord’s map collage (at the top of this page) is one example of a dérive-related artwork; another is Ralph Rumney’s 1957 volume, The Leaning Tower of Venice, a page opening of which is pictured below.

The Assignment: Do a dérive

Option One: Be an urban flâneur

Ideally you will do this with one or two friends. (If they are from the class, even better!) Working with multiple people, and incorporating their different kinds of distractability, will keep distraction at a maximum. It hopefully removes focused intentionality from your wanderings.

Choose a starting point: an address or a street crossing. Then choose a clearly a period of at least one hour. You must wander without any clear destination for at least 30 minutes. Set a timer or keep an eye on the clock. Only after your allotted time is up can you start to wander your way back in the direction of home. (This is why you want to clear twice as much time as your dérive itself.)

(Note that a half hour is not a very long time to wander. If you have the room in your schedule, I recommend you take longer because it takes some time wandering to let go of the idea that there is a purpose or destination. Debord recommended that a real dérive should last an entire day, waking to sleeping.)

Choose one or two statements from Benjamin’s “Theory of Distraction” to keep in mind as you go on your journey.

Then: wander. You may use public transit if you so choose (a good idea is to hop on a random bus ride a few stops) but please do not use your own car, a friends’ car, or a ride-share service during the dérive portion of your journey. (You may, of course, get home from your end point in whatever manner you please.) You may wander into shops or businesses if you want. You are free to make purchases, have food, or grab a coffee. But the fact of where you get food or coffee should not be pre-planned. And your visits should not be goal-oriented and should instead focus on wandering, exploring, absorbing, and following your distraction where it leads you.

Option Two: Do a digital dérive

For this option, follow the same rules as above, but your wandering ground is not the city, but, rather… the 🌐 World Wide Web 🌐.

Again, this activity is better done with a friend. (You could ask a friend, family member, or a roommate to join you, or collaborate with one or more people from your learning group. If you can’t get together in person, you could organize a Zoom and share a screen!) Making your digital dérive into a social activity distinguishes it from the typical kinds of distraction we experience on the Internet. In this case, you and your friend should share one single screen and make your choices about what to click next together, collaboratively.

Again, choose a passage or two of Benjamin’s “Theory of Distraction” to think about while you wander.

The rules:

1. Clear at least 40 minutes on your digital dérive.

2. Use a laptop or desktop computer, rather than your phone.

3. Use the Private Browsing or Incognito Mode on your browser, so that your browsing isn’t influenced by your typical patterns of use. (In most browsers, go to File > New Private Window.)

4. Ensure you are logged out of accounts (such as Google, YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, etc.) that provide customized feeds and content delivery. Stay on the “Open Internet.”

5. Don’t use ChatGPT, Claude, or any other AI-powered or AI-adjacent chatbots at any point in your digital dérive!!! These tools can give “randomness,” but not of the right sort. They are too “smooth”: they don’t provide the sense of total disjuncture that a true dérive requires.

How to get started:

1. Choose a random starting point: A great spot is the Wikipedia main page, or a Google Search of a random word, event, historical figure, or so on.

2. Follow links. Your main job is to take in what you see and then follow your may read the page aloud together, browse images, and so on, or you may simply skim and click on the next thing that sounds interesting. Just keep wandering. Follow your distraction.

3. Take a few screenshots of anything interesting or strange.

4. I would personally avoid clicking on ads, because they usually take you somewhere boring. However, weird Internet ads can be very entertaining and are worth observing and even screenshotting.

5. You may get stuck in “walled” or self-contained sites that never or rarely link outside themselves, such as TikTok or YouTube. If you find yourself there, limit your wandering on that platform to about ten minutes. Then return to search bar.

5. When to return to the search bar: Return to Google, the Wikipedia Main Page, or your preferred keyword search in the following cases:

— when you reach a dead end (a page with no links)

— if you end up stuck on one particular platform (see #3) for more than 10 minutes

— if you find a word, phrase, or idea that you absolutely must google in order to best follow your distraction or keep the spirit of absurdity and randomness going

— if find you are losing the feeling of absurdity and randomness and you need a reset.

What to turn in:

For either the urban or digital options, turn in two things. (Unless the formatting if Part 1 forbids it just stack the two parts on top of one another in one Google Document, with a heading over each part labeling it as Part 1 or Part 2.)

Part 1: “psychogeographic report”: You may turn in any combination of images and words that you feel captures the “vibe,” the weirdness, the absurd contrasts, and the distractability of your journey. It could be a collage, like Debord’s or Rumney’s, a hand-made drawing, or whatever you like. It doesn’t have to fully explain what you did or include everything–just try to capture the spirit of it in whatever way feels natural. The easiest option is to just post some of the photos or screenshots you took, and along with a few of the funniest or weirdest things you noticed or did. But you are also welcome to get very artistic or experimental with this!

If you did your dérive activity with another student from the class, you may collaborate on your “psychogeographic report.” In this case, each of you should put the full report in your individual google folder(s), and note that it was a collaboration and credit your collaborator!

Part 2: short reflection: Write a short, open-ended reflection of about 200 words: You can tell us anything you want to about your journey that didn’t make it into your “psychogeographic report,” or explain anything in the report that might need explanation. If the basic details do not appear in part one, include your starting point, the length of time you wandered, and where you ended up. You may also reflect on how your experience makes sense with your chosen passage from Benjamin, or any other ideas from the course, or contrast it with your previous “Have an Experience” project.

Due Tuesday, November 18 at 11:59 PM